Slate Run Farm is operated by the Columbus Metroparks system. It's a small working farm with real animals and crops, manned by a contingent of park employees and volunteers. You can find more information at the Metroparks webpage or at the Friends of Slate Run Farm volunteer organization.

The farmhouse and barn are original structures bought in the 1980s and "demodernized" to the 1870s. Both structures are large and luxerous compared to the log structures inhabited by earlier waves of settlers. Canals and the railroads have made farming commercially viable, and new devices allow much more to be done with a similar imput of labor.

The farm is typical of many homesteads one passes on the country roads of Ohio.

The front parlor is a place for entertaining guests. One book I've read suggests that it wasn't used much for everyday family affairs, sort of like a front room in a modern suburban house. Ohio houses are no longer lit by tallow candles or grease lamps: Colonel Drake's discovery at Oil Creek has made kerosene a cheap and commonplace replacement for whale oil. City houses at this time use coal-gas nozzles for light, and electric filament bulbs are a few years away. My guess is that neither gas nor electric lines will reach this area for 20-30 years.

A popular entertainment device of the 19th Century, the stereoscopic viewer. This device immerses the viewer in a "virtual reality" of distant and exotic lands.

A detached stone root cellar stood behind the farmhouse. This vent from the upper level of the structure allows air to flow into the room.

Jars of preserved and pickled fruits and vegetables line the shelves. The Mason Jar is a new food storage technology available to the housewife of the late 1800s. Earlier food preserves relied on earthenware pots or barrels of salt.

Another method of food preservation: smoked meat hanging in the smokehouse. Pots of charcoal or smouldering wood fill this wooden shack with smoke. Again, an improvement over salting meats, but an older one: Governor Worthington's 1807 estate also has a smokehouse.

A dog-powered treadmill for powering small devices like butterchurns?

The barn loft, a massive enclosed space stacked with straw and hay bales.

A view of the threshing floor. The barn at the Worthington estate may date to earlier in the century: it is more open at the ground floor and keeps the animal stalls on a lower level.

The barn doors open onto a central corridor with animal stalls to either side.

Another new technology: the chain pump is a hand cranked device that conveys a constant stream of water into the nearby trough. Earlier in the century only sailing ships would have had a device like this. (Never mind my fingernail...)

Horses provide an important source of power for equipment on the farm. Steam powered tractors are beginning to appear but are expensive and less reliable. A horse can have a useful life of 30 years, better than many tractors in the future.

A team of three horses pull the plow through the furrows. A typical farmstead would consist of 120 acres: half planted with corn and half with wheat. Again, observe the state of the art technology: the new riding plow allows a farmer to save his feet.

Piglets, two months old I believe. Hogs are the mainstay of farming in the 19th century. Now, the farmers no longer let them loose in the forest (or town...) to "root hog, or die" on acorns as their fathers and grandfathers did.

Piglets.

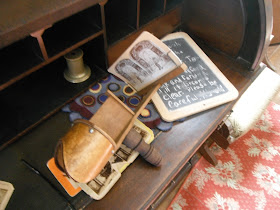

A slate tablet tracking feed for the growing animals. In the 1870s science and technology are having a bigger influence on farm production thanks, in part, to Federal Land Grant colleges like the newly founded Ohio State University.

Forge. The horses and farm implements require a well-stocked blacksmith shop to keep things maintained. The smith of the 1870s has a much more efficient set up than his predecessor-- gone are the massive bellows, replaced by a small, hand-cranked fan.

A beehive. European honeybees aren't native to North America, and wild swarms had only reached the Ohio and Mississippi Valley by the early 1800s. These ones are used to pollinate the nearby fruit trees.

Even more cutting edge technology: a cast iron stove back in the farmhouse. The 1870s housewife no longer spends most of her day spinning yarn or tending an open hearth (the hearth in this kitchen has been blocked up). The stove contains a wood fire in the firebox on the right side. On the left is a reservoir for hot water. There is no thermostat on this stove: it takes experience to detect how hot the oven is for baking.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.