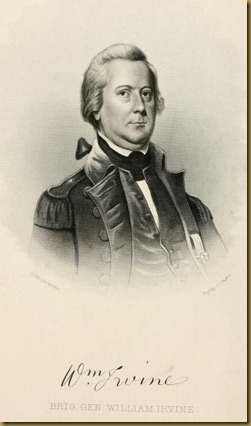

Brigadier General William Irvine, who ordered William Crawfords ill-fated expedition in 1782.

The surrender of Lord Cornwallis’ army in October 1781 at Yorktown all but ended the war in the east. However, attacks against settlers along the Ohio River and in Western Pennsylvania continued. Indians, including the Miami and the Shawnee, had been fighting white encroachment since Lord Dunmore’s War in 1774. During the American Revolution they allied themselves with the British and Loyalist forces. Loyalist forces, such as William Caldwell’s Western Rangers often accompanied and fought alongside the Indians. Brigadier General William Irvine, who commanded Continental forces in the west at Fort Pitt, submitted plans for a full-scale offensive against Fort Detroit. General George Washington, the Commander-in-Chief, agreed with him but doubted that the funds could be raised from Congress for such a venture. Instead, Irvine decided to launch a raid on the Indian towns along the Sandusky River in Northwest Ohio. He would do it on the cheap, using volunteer militia who would arm and equip themselves in exchange for two months’ pay.

Some of these militiamen had already been fighting against the Indians. The war in Western Pennsylvania and Kentucky was more like a modern guerilla war in Africa than a contest between two uniformed armies. Both sides raided and burned each others settlements, and killed civilians. In the midst of the violence, the neutral Christian Lenape (Delaware) people—called Moravians after the German protestant sect who had converted them—who lived along the Muskingum River in eastern Ohio found themselves targeted by both sides. British-allied Wyandot and Lenape Indians forced most of them to relocate further west, closer to the Sandusky River (in a settlement called “Captive Town”). However, groups of the Moravians returned to harvest their corn, which they had left standing in the fields near their villages.

A group of such harvesters found themselves surrounded and captured by a company of Pennsylvania militia led by Lieutenant Colonel David Williamson. The militiamen were pursuing a group of raiders who were thought to be taking refuge in the deserted town of Gnadenhutten, and found the peaceful Indians instead. This had happened once before, and Colonel Williamson had captured the harvesters and brought them back to Fort Pitt, only to have them released immediately at General Irving’s orders (Butterfield, 36). Now Williamson held a council of war. The militia resolved to kill all their captives—although some refused and deserted. The captives were informed of their fate and executed en masse the next day—28 men, 29 women, and 39 children. General Irving, perhaps concerned that something like this might happen, had sent a messenger to warn the Moravians about Williamson’s men—but of course he arrived too late.

The Gnadenhutten Massacre, predictably, kindled more violence along the frontier. General Irving issued a call for volunteers, and more than 480 men responded. He convinced a veteran officer, a personal friend of George Washington’s by the name of William Crawford, to come out of retirement to lead the expedition. Their objective was to strike at the towns along the Sandusky River, burn crops and huts to deny the hostile Indians a base of operations, and defeat any force of British or Indians that attempted to stop them. According to General Irvine’s orders:

The object of your command is, to destroy with fire and sword (if practicable) the Indian town and settlement at Sandusky, by which we hope to give ease and safety to the inhabitants of this country; but, if impracticable, then you will doubtless perform such other services in your power as will, in their consequences, have a tendency to answer this great end. (Butterfield 69-71)Irvine was also careful to specify that if any captives were to fall into American hands who could not be transported back to Fort Pitt, they were to be paroled and set at liberty.

The expedition did not go well. Although the Americans meant to cloak their preparations in secrecy and surprise the Sandusky towns, the British at Fort Detroit had known they were coming as early as April. By the time the mounted column finally moved into the Ohio country in the last week of May, villages along their route had been abandoned and loyalist rangers under Captain Caldwell had joined the parties of warriors who were preparing to defend their territory.

On June 4, Crawford’s column met a band of Delaware Indians led by Captain Pipe. The Delaware were outnumbered but knew that more British and Indian forces were nearby. They occupied a grove of trees on the open prairies near modern-day Upper Sandusky, Ohio. Crawford’s men dismounted and forced the Indians out of the grove after a hard fight. By 4 in the afternoon, Captain Pipe had been reinforced by Chief Dunquat’s Wyandot and Mingo warriors, and the tide of battle turned. The Indians were able to outflank and surround the Americans, using the tall grass of the prairie for cover. Captain Caldwell and his rangers, about 100 strong, were also present on the battlefield. Both sides lost about a dozen and a half killed and wounded.

By midday on June 5, Crawford realized that he could not defend the copse of trees that his men were calling “Battle Island”, and decided to break out and escape during the night. As his men moved off, the colonel remained behind to try to find his relatives and to help move the wounded. In the darkness his party became separated from the main body of American troops. Crawford and a few companions moved south on foot for a few miles before they were met and captured by a Delaware war party.

On June 6, the remaining American troops—about 300 men—fought a rear-guard battle with pursuing British and Indian forces near the headwaters of the Olentangy River. A small group of men under the notorious Colonel Williamson rallied and held off the Indians long enough to secure a retreat. By the time the survivors reached their point of departure—Mingo Bottom on the Ohio River bordering Pennsylvania—about 70 men were missing, killed, or wounded.

Enraged by the Gnadenhutten Massacre, the Delaware and other Indians were not giving quarter to the wounded and prisoners they took in the battle. Some men were scalped and killed on the battlefield, while others were taken back to the towns and executed. After their capture on June 7, Crawford and 12 other prisoners were taken to a Delaware town near Tymochtee Creek under the control of Captain Pipe. Their faces were painted black as a sign of condemnation. Although Simon Girty and Matthew Elliot—representatives of the British Indian Department—tried to buy Crawford’s freedom, the Delaware were determined to make an example of the American leader.

Site of Colonel Crawford’s execution, near State Route 23 in Northwest Ohio.

Crawford and an American physician, Dr. John Knight, watched as nine of the other captives were tomahawked or beheaded, most by the Delaware women and boys. Crawford was then stripped naked and tied to a post. A bonfire was kindled a few yards away, and the crowd tortured him for over two hours before he was allowed to die.Dr. Knight survived to tell of Crawford’s execution. As he was being led to another town for his own demise, the army officer and surgeon knocked his guard on the head and walked back to a friendly settlement—it was not until July 4 that he reached the safety of Fort Pitt, severely malnourished from surviving on wild gooseberries and ginger roots (Butterfield, 373).

1782 became known as the “bloody year” in the history of the Ohio valley settlements. Emboldened by their victory over Crawford’s expedition, war parties from the Northwest tribes ventured into Western Pennsylvania and Kentucky. One such raid under Captain Caldwell dealt the Kentuckians their worst defeat of the war at the Battle of Blue Licks.

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 stopped hostilities between the British and Americans, but war soon flared up again in the northwest. The wars fought between 1785-94 and 1811-15 eventually saw the defeat and marginalization of the Ohio Indian tribes, but not before more American defeats such as that of Harmar’s expedition in 1790, St Clair’s defeat in 1791, Brownstown in 1812, and Frenchtown in 1813.

As for the Moravians, they moved to the relative safety of Canada following the war. In 1813, it was to their settlement, Moravian Town, that William Henry Harrison pursued the Shawnee leader Tecumseh and British Major General Henry Procter's forces. After the climactic American victory, Harrison ordered his men to set fire to the Christian Indian settlement--which he claimed had been used to store war material. The Moravians made a petition to Congress in 1814 for restitution. "...All their fair prospects have at once been blasted by the total destruction of their settlement by the Army of the United States..."

I don't know whether the Moravians were ever given reparations by the United States Government following the war. Most civilian requests for reparations from both sides were ignored or denied. Thus, the tragedy of an American revolutionary officer, and that of a peaceful group of agricultural Indians, became entwined during the forging of the modern Middle West.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.