I was looking through a collection of letters from the early 1800s this afternoon and stumbled upon one that seemed out of place. While the rest of the letters belonged to a prominent Ohio frontier family, written between 1812 and 1817, I found one from 1815 that was addressed to a Jacob Bowman:

Bridgeport Oct the 14- 1815

Mr. Jacob Bowman

Sir,

In answer to you inquiries concerning steam boats I enclose the following statements.

First

The steam boat Enterprise built by me in this place cost with her furniture when complete about eleven thousand dollars (crossed out: "her burden when")

She will carry about thirty tons.

Secondly

The steam boat Dispatch of twenty tons burden cost about 5300 dollars both of the above boats are propelled by one wheel in the stern or hinder part of the boat.

The patent (?)right for one boat (to run on the lake) of 50 tons would cost about 1500 dollars.

The engine would cost at this place 5000 dollars.

The whole expense of a vessel of 50 tons would be about 12,000 dollars perhaps more or less.

Small vessels cost much more in proportion to their size than large ones.

Your Servant Daniel French

The first steamboat on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers made its first voyage in 1811, the year of the great New Madrid Earthquake. A bit of Google research reveals that the Enterprise was one of the first steamboats to ply the Western rivers, built by Henry Shreve and Daniel French (French was the designer) in 1814. Shreve took her down to New Orleans (making the Pittsburgh to New Orleans trip in 14 days) with supplies for Maj. General Andrew Jackson’s army, then defending the city.

After the War of 1812 (when Fulton designed and built a “steam frigate” Demologos) ended, shipbuilders and businessmen were already interested in building fleets of the new type of vessel for trade on the inland rivers and the Great Lakes. However, Fulton (who died in 1815) and his partner Livingston had a monopoly on steam boats. Thus, French mentions the payment of 1500 dollars per boat.

Not that French and Shreve paid the royalty. In fact, they were an early breed of “software pirates”, who broke the monopoly of the Fulton group on river steam boating by refusing to pay. The lawyers tried to impound the Enterprise at New Orleans in 1815, but Shreve paid bail (and then General Jackson commandeered it for military use). By 1816, the monopolists had given up.

This is one extreme of the intellectual property rights spectrum: the inventors had a complete monopoly on steam navigation that threatened to stifle the growth of an important shipping industry. However, the geography was too vast and the technology was too fast for the lawyers.

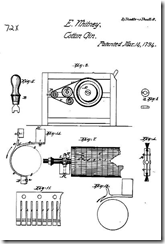

The opposite extreme was Eli Whitney’s cotton gin. Invented in the 1790s to help out the widow of a Revolutionary War general, the gin was supposed to be manufactured by Whitney’s partnership, with exclusive rights to make and sell the important machine. But southern mechanics and planters eagerly copied the invention, without paying any royalties to Whitney.

Without any control over his intellectual property, Whitney spent years in courts trying to get some part of the profits that his gin was reaping. In the end, he turned to arms making, and manufactured muskets for the United States (many of which were used during the War of 1812). He claimed to have developed a system of interchangeable parts for these muskets, a harbinger of mass production.

So it seems like early American history provides two examples of intellectual property rights issues: the steam boat, in which case a overly-powerful monopoly nearly stopped technological development; and the cotton gin, in which case there was no reward for the inventor, who moved on to a different industry entirely.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.