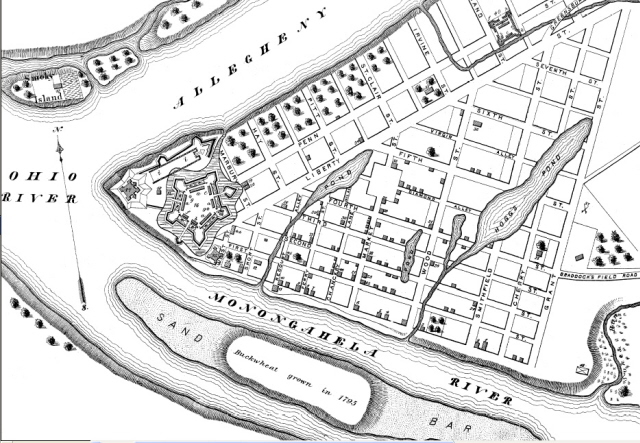

Early in 1813 there was a debate between American naval officers whether the US fleet on Lake Erie should be built at Black Rock, near Buffalo New York or at Erie, Pennsylvania. There were disadvantages to both places. Erie was only a small village with no facilities for shipbuilding, and no defenses. A sandbar across the mouth of the sheltered bay there prevented any vessel larger than a gunboat from sailing out into the lake. Black Rock (which is now more or less subsumed into modern urban Buffalo) was the site of the existing US shipyard on Lake Erie, and a brig and several smaller ships had already been gathered there by Lieutenant Jesse Elliot. However, it's disadvantages were even worse: the guns of British batteries on the Canadian side of the Niagara River could range the shipyard, and the strong river current meant that any vessel launched there would have to be towed upstream by teams of oxen--again under the guns of the British forces. And it was within easy reach of any British raiding parties from the opposite shore who could burn up several months work with a surprise attack.

Sailing Master Daniel Dobbins was an early resident of Erie and had sailed there with his schooner Salina before the war. He thought that ships could be built in the sheltered bay and, once ready could be gotten over the bar and into the lake. But to arm them, cannon had to be brought from the naval station at Black Rock, and British ships patrolled the lake. This meant that Dobbins spent the spring of 1813 essentially smuggling large pieces of ordnance over stormy waters past the British ships. Here is one such journey, which probably occurred in May of 1813 (from Captain William W. Dobbins, History of the Battle of Lake Erie, 1876):

As a sample of one of these hazardous trips, he started to bring up two long 32-pounders, weighing 3,600 pounds each. In the way of a craft, he was only able to procure an old "Durham boat", so-called, which had been used to boat salt from (Fort) Schlosser to Fort Erie; and after fitting her up as best he could, with timbers placed lengthwise in her bottom, got the guns on board, tracked up the rapids of Niagara River and started for Erie, having a four-oared boat in company. He kept near the American shore, but dare not show his sail except at night. When off Cattaraugus, in the night, it came on to blow heavily from northwest, and in order to keep her off the beach, they made what sail they could with two planks for leeboards, and, after a struggle, succeeded in getting an offing. But their troubles were not ended: the great steering-oar unshipped, and the boat fell off into the trough of the sea. The heavy rolling soon carried away the step of the mast before they could get the sail down. But the repairs were soon made and they got sail on again, when it was found she was leaking badly, caused by the heavy rolling, with so much weight in her bottom, and likely to founder. As the old maxim has it, "Necessity is the mother of invention," Mr. Dobbins took a coil of rope they had on board, and passing the rope round and round her, from forward to aft, and heaving the turns taut with a gunner's hand spike, thus managing to keep her afloat, with all hands bailing. At daylight they found themselves some ten miles below Erie, with two of the enemy's cruisers in sight in the offing to windward. However, the wind had veered more to the eastward, and they made port with a fair wind--their consort, having parted company with them in the night, safely made port, and reported Mr. Dobbins' boat lost.Durham boats are most famous for having been used by George Washington in his crossing of the Delaware River. They were designed for use with heavy cargo, such as the pig iron shipped on the Delaware River from the Durham Ironworks.