Monday, May 12, 2014

Get Thee to the NYPL...

Sometimes I find references to primary sources that ended up in archives or libraries. This one ended up in the New York Public Library in 1914, where it remains to this day. Ohio Historical Society has a copy of the microfilm in it's archives, though somewhat worse for wear:

Saturday, December 17, 2011

Captain Shole's Diary: A Trip down the Lake

Today's passage comes from the journal of Captain Stanton Sholes, 2nd Regiment US Artillery (transcribed by Richard C. Knopf, 1956). Sholes spent much of 1813 stationed with his artillery company in Cleveland, Ohio--a tiny village back then. He built the first hospital there (a log cabin constructed without any nails or ironwork), and established a gun battery to protect the flotilla of transport boats being constructed by Major Thomas Jessup (who later went on to bigger things) consisting, apparently of one six-pounder. The passage has been corrected for grammar and spelling except where noted.

Monday Sept. 13th

This day commences with fine weather. The quartermaster give (sic) encouragement to me that I should have a passage in a boat that would sail the next day for the Portage (Portage River in Northwest Ohio, near the Marblehead Peninsula --DW), laden with ammunition for the N.W. Army.

Saturday, October 15, 2011

Font of Knowledge

Check it out:

Saturday, April 9, 2011

Classified Ads from the Franklinton Freeman's Chronicle, 1812-13.

Saturday, March 12, 2011

Steam Boating and Intellectual Property Rights

I was looking through a collection of letters from the early 1800s this afternoon and stumbled upon one that seemed out of place. While the rest of the letters belonged to a prominent Ohio frontier family, written between 1812 and 1817, I found one from 1815 that was addressed to a Jacob Bowman:

Bridgeport Oct the 14- 1815

Mr. Jacob Bowman

Sir,

In answer to you inquiries concerning steam boats I enclose the following statements.

First

The steam boat Enterprise built by me in this place cost with her furniture when complete about eleven thousand dollars (crossed out: "her burden when")

She will carry about thirty tons.

Secondly

The steam boat Dispatch of twenty tons burden cost about 5300 dollars both of the above boats are propelled by one wheel in the stern or hinder part of the boat.

The patent (?)right for one boat (to run on the lake) of 50 tons would cost about 1500 dollars.

The engine would cost at this place 5000 dollars.

The whole expense of a vessel of 50 tons would be about 12,000 dollars perhaps more or less.

Small vessels cost much more in proportion to their size than large ones.

Your Servant Daniel French

The first steamboat on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers made its first voyage in 1811, the year of the great New Madrid Earthquake. A bit of Google research reveals that the Enterprise was one of the first steamboats to ply the Western rivers, built by Henry Shreve and Daniel French (French was the designer) in 1814. Shreve took her down to New Orleans (making the Pittsburgh to New Orleans trip in 14 days) with supplies for Maj. General Andrew Jackson’s army, then defending the city.

After the War of 1812 (when Fulton designed and built a “steam frigate” Demologos) ended, shipbuilders and businessmen were already interested in building fleets of the new type of vessel for trade on the inland rivers and the Great Lakes. However, Fulton (who died in 1815) and his partner Livingston had a monopoly on steam boats. Thus, French mentions the payment of 1500 dollars per boat.

Not that French and Shreve paid the royalty. In fact, they were an early breed of “software pirates”, who broke the monopoly of the Fulton group on river steam boating by refusing to pay. The lawyers tried to impound the Enterprise at New Orleans in 1815, but Shreve paid bail (and then General Jackson commandeered it for military use). By 1816, the monopolists had given up.

This is one extreme of the intellectual property rights spectrum: the inventors had a complete monopoly on steam navigation that threatened to stifle the growth of an important shipping industry. However, the geography was too vast and the technology was too fast for the lawyers.

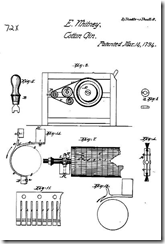

The opposite extreme was Eli Whitney’s cotton gin. Invented in the 1790s to help out the widow of a Revolutionary War general, the gin was supposed to be manufactured by Whitney’s partnership, with exclusive rights to make and sell the important machine. But southern mechanics and planters eagerly copied the invention, without paying any royalties to Whitney.

Without any control over his intellectual property, Whitney spent years in courts trying to get some part of the profits that his gin was reaping. In the end, he turned to arms making, and manufactured muskets for the United States (many of which were used during the War of 1812). He claimed to have developed a system of interchangeable parts for these muskets, a harbinger of mass production.

So it seems like early American history provides two examples of intellectual property rights issues: the steam boat, in which case a overly-powerful monopoly nearly stopped technological development; and the cotton gin, in which case there was no reward for the inventor, who moved on to a different industry entirely.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Thomas Morgan: 1812 Veteran

After returning to Lebanon Ohio in 1814, Captain Daniel Cushing wrote Morgan a certificate noting his wounds. Cushing drowned in the Auglaize River in 1815. Morgan, like many veterans of the early wars, applied to the government for a pension, but his papers were lost en route. This entry in the official register of the State of Illinois tracks Morgan's efforts in 1844 to have local witnesses vouch that the papers existed, so he could be provided for in his old age.

What makes this passage interesting is that Morgan seems to have seen too many famous aspects of the Northwest campaign (even the Battle of Lake Erie), and suffered wounds which seem out of place for an artilleryman. Cushing's Company of the 2nd United States Artillery Regiment was indeed involved in a close combat skirmish before the Seige of Fort Meigs, but to have been wounded by a tomahawk during Dudley's Massacre on May 5th, 1813, by a falling spar during the Battle of Lake Erie, and finally by an officer's sword during the famous charge of the Kentucky mounted rifles at the Thames, severely tests our credulity. It seems that either Morgan was concocting stories in order to generate more interest in his plight as an aging veteran, or some of the 1812 regular soldiers saw far more action than most sources attest.

Edit: Thomas Morgan was indeed the First Sergeant of Cushing's Company. Whether he was detached from that unit for the variety of missions that his testimony describes is still unclear. I recall McAfee mentioning that Captain Eleazar Wood of the Engineers was involved in the mounted pursuit of some fugitive British officers in the aftermath of the Thames rout, but this doesn't explain how a first sergeant attached to an artillery crew would have gotten into combat with a British officer-- and I haven't seen British documentation of which officers, if any, were killed at the Thames.