Fortunately, I made it back to the Interstate and into Cincinnati itself without issue. The city itself, scalloped and crowded by the majestic hills of the Ohio valley, is quite different than Columbus’ lazy expanse. Switching on the GPS, I threaded my car through a maze of unfamiliar intersections. Shortly thereafter, I arrived at the half-dome of Union Station, on the western edge of town.

The train station in its 1933 splendor. One almost expects to see zeppelins circling overhead.

The terminal still houses an Amtrak station, as a sad remnant of the American passenger rail system. Most of the building is taken up by three museums, a special exhibit space, and a large screen theater. The museum complex is known as Museum Center.

The central atrium was crowded with families heading to the children's museum in the basement. I headed for the wing where the history museum was housed. After descending a ramp, I emerged into the centerpiece of the exhibit: an enormous model railroad layout of Cincinnati circa 1900-1940s.

Trains bustled loads of WWII vehicles and boxcars across the waterfront as a sidewheeler pulled up to the quay. The old bridge not only supported street traffic, but also a trolley line. The streetcar lines stretched like a steel web through the city, and even up hillsides……Via an elegant system of elevators. Eager to see more, I left the train exhibit for now and went downstairs.

One of the original streetcars rested on the next level down.

I can’t imagine this kind of elegance in a modern city bus, but for commuters of the early 1900s, vanished wood and brass were ordinary environmental features.

The intermediate level was filled with exhibits relating to Cincinnati’s role in the Second World War, the home front, etc. But I was less interested in the Cincinnati of the 1940s as in the frontier town of the 1790s-1860s. I descended still lower: time seemed to run backwards until I reached the beginning.

At the dawn of written history, which as far as we know reached these parts with the first Jesuit explorer-missionaries, the Ohio valley was mostly empty. The great mound-building civilizations that had dominated the country for a thousand years had fallen to the smallpox that raced inland from the points of first contact with Europeans.

Woodland Indian nations such as the Shawnee inhabited the forests, conducting trade, agriculture, hunting and warfare as they’d done for centuries. However, the first figures I saw betrayed European influence. The textiles, silver, and iron implements that they wore or carried had come from white traders. Their way of life was already irrevocably changed…

I descended further, through a tableaux suggesting the unbroken gloom of the first forests. The air was filled with the sounds of birds and wildlife.

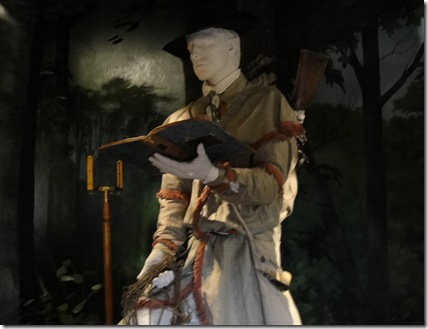

At the other end of the forest tunnel, a solitary figure dressed in a hunting frock checked his notebook. The land surveyors were truly the outriders of western expansion. Armed with a compass, a Jacob’s-staff, and a chain, they marked out the virgin land for clearing and settlement. George Washington was a land speculator before he was a general or statesman, and others like him created empires in the wilderness.

I like to think of surveyors as the Silicon Valley nerds of the 1790s. Surveying was a skill in demand just like computer science is today, and the code they wrote shaped what we now think of as the cities and roads of the Midwest.

Still deeper into the basement I went, and time turned about and lurched forward. I stumbled through a rude log cabin. Whoever inhabited it was well-off, since he had a writing desk, silverware, and a chair instead of a log to sit on.

The surveyors and settlers needed protection. In the Fort Washington barracks a private of the 1st US Infantry Regiment prepared to go on duty.

Across the passageway, a Shawnee warrior looked on disdainfully. From the 1770s and 80s Kentucky was known as the “dark and bloody ground” for its brutal, ongoing conflict between settlers and Native Americans. By the 1790s, this conflict moved north of the Ohio River.

Both the United States and Great Britain sought the allegiance of Indian tribes in the Ohio country. They minted peace medals like this one for distribution among warriors. Dei Gratia means “by the grace of God.” After a series of defeats, a United States army led by General Anthony Wayne forced the Indian tribes of Ohio to give up their claim to lands in the southern half of the state.

A gallery of prominent Cincinnatians was next. The talking heads were illuminated in turn as they engaged in a conversation about the young metropolis.

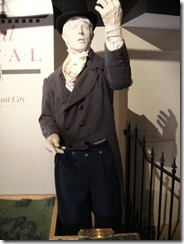

One of the early movers and shakers in these parts was William Henry Harrison. “Old Tippecanoe” is best known for being the shortest-lived president, thanks to his Whig compulsion to make a speech bareheaded. His negotiations with the tribes of the region were formative in creating what we now know as Ohio and Indiana, at the expense of the Indians.

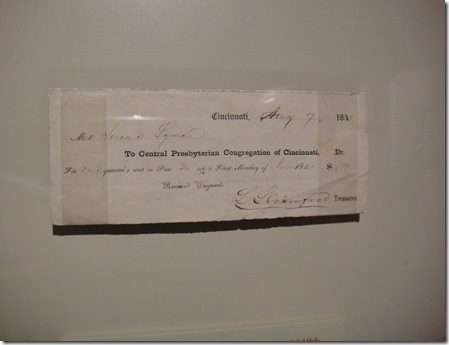

A ticket for a pew. I didn’t know that churches used to rent pews in order to raise funds.

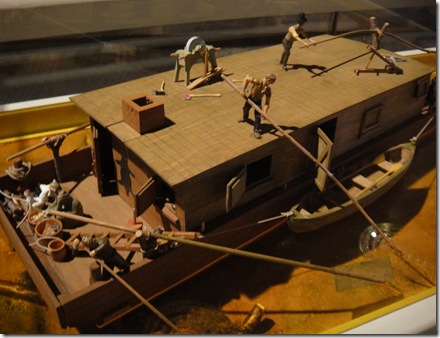

The Ohio River quickly made Cincinnati an important inland port. Flatboats like these served as “arks” to bring settlers from the east, and then to bring produce down to market in New Orleans. They pretty much drifted with the current. How did the farmers get back up? They hoofed it north along the Natchez Trace from Mississippi, hopefully not getting mugged or killed by robbers along the way.

Keelboats moved up and down the river in the years before the first steamboat arrived in 1811. This is a canal boat, which has a little more superstructure and a blockier hull than a keelboat. Canals were first contemplated by George Washington in his real-estate days, and were finally built between the 1820s and the 1850s. Packet boats like this one moved between the lakes and the Ohio River at a steady pace of 2 miles an hour.

The canals could be seen for many years after the boats had been abandoned for railroads.

One early Franklinton resident remarked that whatever the town exported had to go to market on its hooves. One of the easiest animals for early settlers to keep were pigs. They could be set to graze on acorns in the forest, and herded to distant markets. Cincinnati became known as a place for processing hogs, and this sketch shows a young lady caught unawares by a fleeing pig.

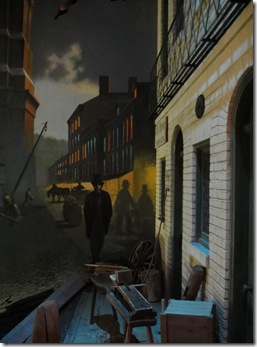

Deep within the sub basements of the museum, I found a large room dressed up as an early Cincinnati street. The hogs were fortunately absent, replaced by strollers.

Advancing through the square, I reached the dockside, enshrouded in twilight.

A steamer was tied up at the riverbank, with roustabouts busy unloading a downriver cargo.

A few steerage passengers waited impatiently for the boat to sail. One of the coolest things about this area was that the sidewheeler was made to float on real (though shallow) water!

On the main deck, a pair of engines drove the paddlewheels. The biggest difference between river boats and lake or seagoing steamers were the engines. The latter had vertical pistons rocking a pair of beams to transfer power to the paddlewheels. River boats had to be very shallow-drafted, and all the machinery was placed on top of the main deck instead of under the waterline.

I left the museum after spending some more time mesmerized by the model city, somewhat disoriented by the layers of history through which I had delved. The Cincinnati History Museum had definitely proven worth the admission.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.