Fort Detroit. A scale diorama depicting Detroit in the 1790s before it was turned over to Americans; the Fort and pickets around the town are identical to the defenses as they existed in 1812. The British burned the fort when they retreated from the area in 1813, but the Americans rebuilt it and renamed it Fort Shelby, pretty much on the original plan.

Last weekend, we had planned to stage a big, reenactors-only wargame version of the Battle of the Thames, but rain intervened. So I found myself getting on the road home mid morning on Sunday. Unlike Benson Lossing, the 1860s historian and travel writer who toured the battlefield before writing his epic War of 1812 narrative, I wanted to visit the nearby village of Moraviantown. For some reason, the local police had closed the road from Thamesville and I was forced to turn back. (The Moravians were Christian Indians who had originally settled in eastern Ohio: following a massacre which I've detailed elswhere in this blog, they moved to Upper Canada. General Harrison had their village burned down, because it supposedly harbored supplies and weapons for the British.)

I had been wanting to visit the Detroit Historical Society--near the campus of Wayne State University in urban Detroit-- for a while, and I jumped at the opportunity this time.

|

| Abandoned automobile plant. Albert Duce via wikipedia. |

Detroit has fallen on hard times, in fact it has been in a constant state of decay since before I was born. However, the Big Three automakers are still headquartered in the general vicinity, and seem to be doing all right, considering the recession. Detroit deserves better. For all of us who grew up in rustbelt cities around the Great Lakes region, it has always stood as a figurehead of a vanished industrial, blue collar civilization. In Michigan, or so I hear, economic development has migrated towards Grand Rapids, and non-union employers like Amway. Detroit is therefore a kind of avatar for American labor and heavy industry in general.

My interest, though, is mainly in the old Detroit, before the Industrial Revolution(s) had really swept across the American Midwest. Detroit was built on the fur trade: it was really the gateway to the upper Great Lakes, a place where the government and powerful trading companies like Jacob Astor's firm could set up warehouses (called factories) to exchange manufactured goods for furs. The War of 1812 transformed Detroit, as it did many frontier towns, by eliminating British influence from the American northwestern territories, clearing the road for Astor and other American firms to dominate the fur trade.

|

| Lewis Cass in the 1850s. |

For many years after the war, a former Ohio general named Lewis Cass presided over the territory. Cass was a big deal-- he served as Territorial Governor until 1831, as US Secretary of War, and as Senator once Michigan became a state. He was only one of several Northwestern Army officers to play important roles in the development of the frontier. In the wake of the Thames Campaign both he and fellow Ohioan (and future Ohio governor) Duncan McArthur were placed in charge of occupying former British-held territories. Cass graduated directly from command of a brigade of 12-months regular infantrymen to being the Governor of Michigan in 1813.

.jpg) |

| Duncan McArthur. |

McArthur, after a brief stint at Sackett's Harbor and testifying at the William Hull court martial returned to take up command of the 8th Military District, with headquarters at Detroit. Both men ended the war where they had started it: Cass and McArthur had led Ohio Volunteer Militia regiments as colonels during the debacle of the first Northwestern Army's campaign.

But I digress. When I travel, I take pictures as a reference as well as a souvenir. Since I'm interested in recreating the past as well as educating the public about it, I spend a great deal of time getting pictures of museum exhibits and historical sites wherever I go. This blog constitutes a virtual museum, as well as a commentary on how museum exhbits are constructed and how well they convey whatever information they are meant to communicate.

A young Lewis Cass. Below: the town in fur trading days.

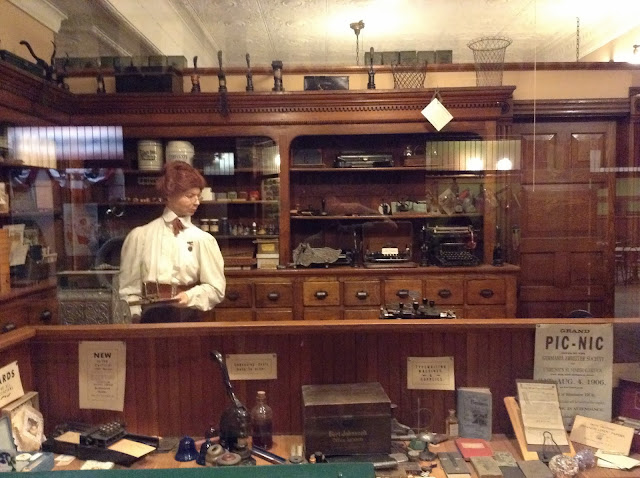

The museum was arranged on three floors, and was free for the public (parking in the rear lot was $5). The basement featured a "streets of yesteryear" walkthough--something I've encountered at Columbus COSI, Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry, Cincinatti's history museum, and many others. This one was fairly elaborate but not well interpreted. Some of the storefronts were simply repositories for old collections the curators didn't have anyplace else to display. Static collections behind glass are inert and can never be wholly successful in engaging the visitor.

The 1840s:

(What's the story here? It looks like a widow is visiting the banker. Is she selling off her dead husbands military land bounty, or getting a loan?)

(The pavement is one of the fun things about "streets of yesterday" type exhibits. It transitions from asphalt, to bricks, then cobblestone, and mud--or in this case, pitch and wood. Chicago had this type of pavement before the Great Fire!)

The 1870s:

The 1900s:

The first floor or main level featured a number of exhibits, including the early history of Detroit, the automobile industry, and a Kid Rock "Rock lab."

The early history section was a broad survey of developments leading up to the city's industrialization in the late 19th century. It featured a handful of artifacts, and more dioramas. Unfortunately, most of the static displays were almost deliberately badly lit with can lights, making photography difficult.

African Americans played an important role in the early years of Detroit. Since the Michigan Territory was free and the neighboring Upper Canada a slave province, in the years before the War of 1812 several slaves escaped from Canada into the United States. A few years later, the traffic would run in the other direction.

The famous steamship Walk-in-the-Water, named after a Huron chief who defected from Tecumseh on the eve of the Battle of the Thames and offered his services to General Harrison. The ship was launched in 1818, a year after her namesake died, and ran from Buffalo to Detroit, until she sank some years later.

There was a two-story exhibit on the auto plants, featuring a 50-foot or so long section of assembly line from the 1970s. Once again, its a static display, so a bit hard to tell what's going on.

On the next floor, there was a large exhibit on railroads. This is a model of a monorail design proposed for Detroit in 1918...

A second model train display had been installed in the basement, near the streets of yesteryear. The lights and model trains (and a train-themed playlist) activate once someone enters the room. One of the trains had a small video camera mounted on it, which displayed in real time on a couple of tv sets mounted above. It was reminiscent of the scene in the Addams Family movie when Gomez Addams takes out his frustrations on his model train set.

All things considered, the Detroit Historical Society is well worth a visit if you're passing through the city, for the perspective it provides on the growth and subsequent decline of the Queen of the Rust Belt.

The early history section was a broad survey of developments leading up to the city's industrialization in the late 19th century. It featured a handful of artifacts, and more dioramas. Unfortunately, most of the static displays were almost deliberately badly lit with can lights, making photography difficult.

African Americans played an important role in the early years of Detroit. Since the Michigan Territory was free and the neighboring Upper Canada a slave province, in the years before the War of 1812 several slaves escaped from Canada into the United States. A few years later, the traffic would run in the other direction.

The famous steamship Walk-in-the-Water, named after a Huron chief who defected from Tecumseh on the eve of the Battle of the Thames and offered his services to General Harrison. The ship was launched in 1818, a year after her namesake died, and ran from Buffalo to Detroit, until she sank some years later.

There was a two-story exhibit on the auto plants, featuring a 50-foot or so long section of assembly line from the 1970s. Once again, its a static display, so a bit hard to tell what's going on.

On the next floor, there was a large exhibit on railroads. This is a model of a monorail design proposed for Detroit in 1918...

All things considered, the Detroit Historical Society is well worth a visit if you're passing through the city, for the perspective it provides on the growth and subsequent decline of the Queen of the Rust Belt.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.