I get really into Halloween each year. It's perhaps the one time of year when society in general celebrates the macabre and the otherworldly. In Ohio, the climate is usually most cooperative in creating a gloomy and evocative atmosphere. What's more, my interest in history dovetails neatly into my abiding fascination with the ghostly, the mysterious, and the supernatural.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is one of the most popular ghost stories since it was written as a short story for Washington Irving's The Sketchbook of Geoffry Crayon, Gent. The protagonist (as well as the other characters in the story) was originally meant to poke fun at certain early-19th Century American stereotypes. The willowy, conniving Yankee schoolmaster arrives, like a carpetbagger, into the rustic, sleepy Dutch community of Sleepy Hollow, New York and angles to get a cushy inheritance by marrying into the well-to-do Van Tassel family. He's foiled when some of the local bloods play a trick on him and scare the schoolmaster out of the county.

Since then, the Ichabod Crane character has been reworked into a New York City police Constable circa 1799 (played by Johnny Depp-- even though the NYPD wasn't established until 1845), and even a Revolutionary War hero himself. But there was a real Ichabod Crane. In 1814, Irving was serving as a staff officer in the New York State Militia. He didn't see any action, but was for a time the military secretary of Governor Daniel Tompkins.

This in itself is really interesting. Tompkins was a Republican, and one of the most important war leaders (since most of the fighting occurred in or on the borders of his state). Regiments and brigades from the New York State militia fought in every major engagement along Niagara border, and the important harbor and navy yards at New York city were mostly garrisoned by volunteers and more militia.

Most Irving scholars write off his involvement in the war, which is indeed strange since he was such an Anglophile. However, he was to write extensively on some aspects of the conflict, including a biography of Captain James Lawrence, an American war hero who had died in a frigate duel in 1813. During his brief service on Tompkins' staff, he was sent to Sackett's Harbor, New York. This small town (it's still a very small resort town on the eastern corner of Lake Ontario) was then one of the largest shipbuilding and naval bases in America. It was the American side of a fantastic naval arms race that had lasted all three years of the war, and whose winner would decide the fate of the Great Lakes. A string of earthen batteries and forts studded with heavy artillery protected the harbor, filled with warships of all shapes and sizes. The most recent of the naval construction projects were the massive 90-gun ships of the line USS Chippewa and USS New Orleans, due to be finished in time to challenge the Royal Navy's own 120-gun behemoth St. Lawrence sometime in 1815.

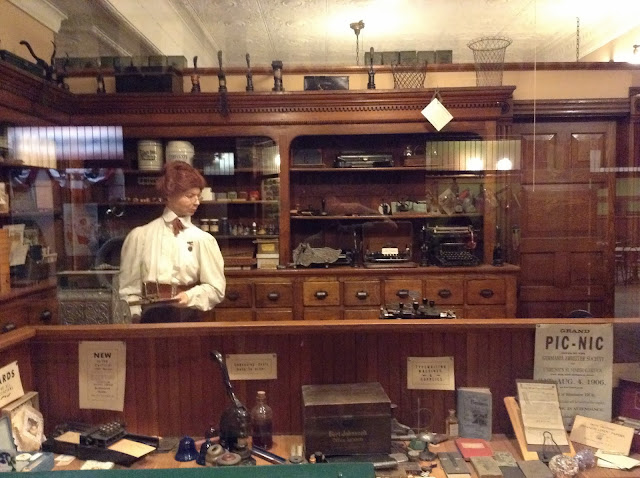

Crane in later life.

There he met an artillery officer named Ichabod Crane. Crane was a former officer in the Marine Corps who had served from 1809 to 1811. When the Army was expanded in 1812 he accepted a commission in the newly-raised 3rd Regiment of Artillery as a captain. Part of the 2nd, and all of the 3rd Regiment (each composed of 20 companies of between 80-100 men) were never equipped with artillery. Since the three regiments of artillery were meant to be foot artillery, they were first drilled and equipped to fight as infantry of the line. As such, a battalion of the 2nd Artillery distinguished itself at Queenston Heights under its Colonel Winfield Scott.

While more of the 2nd Regiment got their artillery field pieces, the 3rd continued to act as infantry and played an important role in constructing and manning the forts of the northern frontier. On March 30, 1814 the three regiments were disbanded and reformed into a Corps of Artillery (which did not, incidentally, include the Light Artillery that remained its own Regiment). Besides organizing battalions of the formerly independent field companies for service on the battlefield, the reorganization meant little for the scattered companies of artillerymen serving in forts and small detachments.

Captain Crane's company served during the 1813 Battles of York and Fort George, probably as infantrymen, before spending the remainder of the war garrisoning Fort Pike--part of the Sackett's Harbor defenses. While many of his colleagues were brevetted for their role in the bloody battles along the Niagara, Crane was promoted to Major for "meritorious service and general good conduct." While he hadn't seen much action, it says a lot about his value as a soldier of this highly technical arm that he was retained as a field officer in the tiny post-war regular army. He was still in the service-- having risen to a full-bird Colonel-- when he died at age 70 in 1857. From the photograph which survives of him in later life, there's little hint of any weird characteristics that might have made him stand out in Irving's memory.

I've perused some of Irving's notebooks from that era, and there's nothing that stands out as relevant to the later ghost story. He doesn't even mention Crane, focusing instead on the journey over muddy roads through what was then a wilderness between Albany and Sackett's Harbor. Perhaps it was just the name that stood out, in an era of ostentatious names (Simon Zelotes Watson, Eleazar Derby Wood, Shadrach Byfield just to name a few off the top of my head). You have to wonder, though, what the real Ichabod Crane must have thought of Irving's story-- let alone the TV and film alter egos that have perpetuated his name.

.jpg)