The centerpiece of the Toledo, Ohio waterfront is a 600-foot long retired iron ore freighter named the Colonel Schoonmaker (formerly the Willis Boyer). She (or he, as the ore boats are sometimes referred as) was commissioned the year before the Titanic, and sailed the lakes until 1980. This past year the venerable ship was moved from her old berth at International Park to a new one just upriver from the I-280 bridge in East Toledo. I was recently able to get a close-up look at the newly restored ship.

The ship has been repainted in her original green and orange colors, with the Shenango Furnace Company logo emblazoned on her stack and at various spots throughout the ship.

This cast iron steering wheel was one of several auxiliary steering stations installed at various points in the ship.

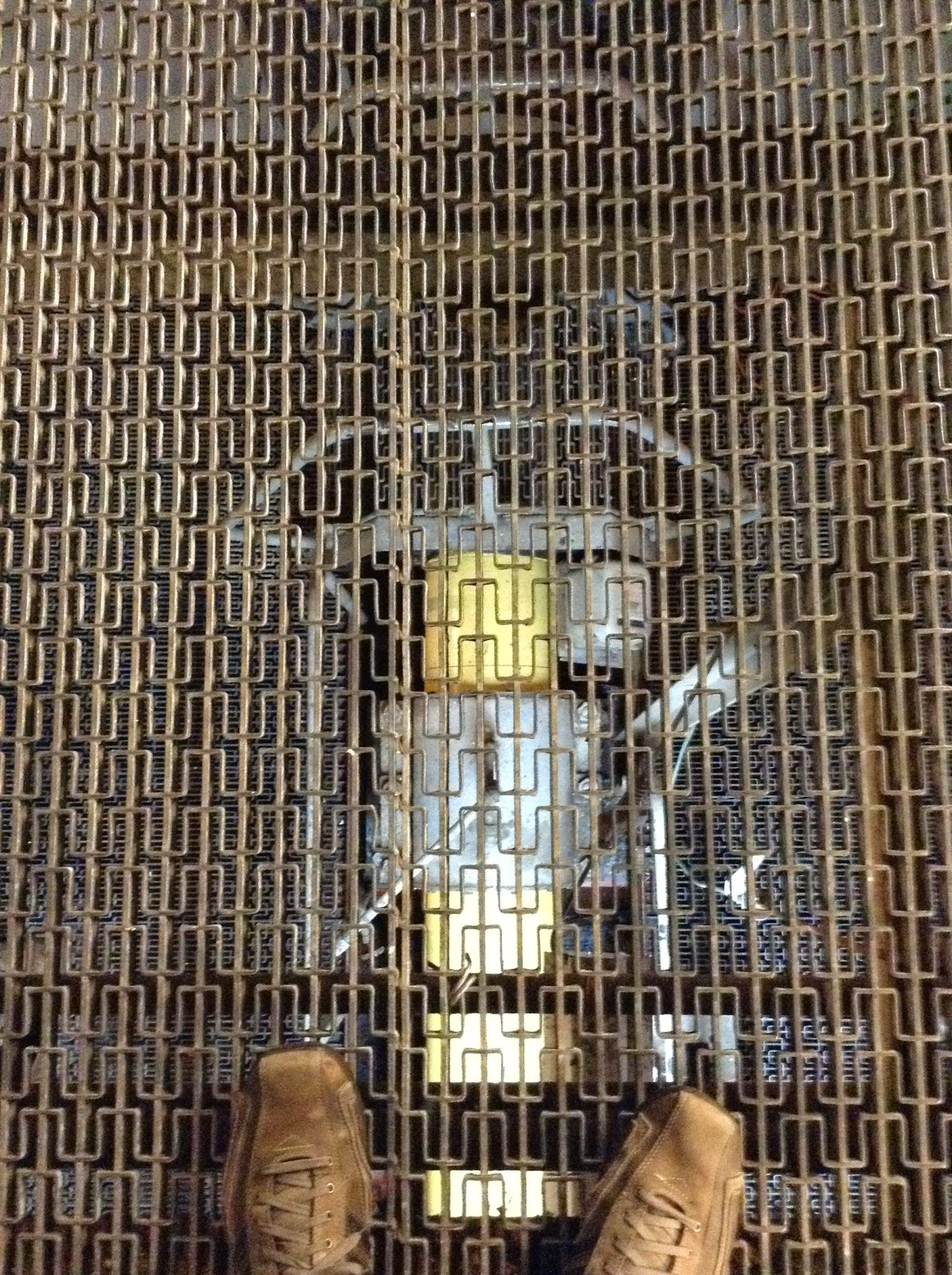

The engine room is a large, open space near the stern of the vessel filled with machinery, pipes, and workshops.

The space seems to extend up several decks and the bottom of the ship, the bilge, lies in shadows under several layers of inaccessible crawlspaces and steel gratings.

Besides the large turbine engine, a refit from her original reciprocating steam plant, there are electrical generators and a water treatment plant to supply the boilers.Looking forward from the engineer's station just forward of the turbine, the ships boilers are a wall of metal, insulation and silver paint. For many years this area was walled off on account of asbestos.

An engine room telegraph, which communicates the captains orders.

The turbine controls.

The engineers station had a little notebook filled with notes from the vessel's last voyages.

The engine itself.

Beneath the engine, the propeller shaft turns the massive screw propeller at the stern of the ship.

Some sort of auxiliary diesel engine near the back of the engine room deck. Probably used as a generator.

At the very stern of the vessel, a large gear turns the massive rudder, powered by a steering engine.

Next, we go up the stairs near this Dutch-door hatch, leading up to the main deck and the stern deckhouse.

The fantail sports an electric windlass, anchor and chain locker for mooring the ship.

The engineers and steward had relatively spacious cabins in the aft deckhouse.

The engineering department crew's quarters-- still relatively spacious.

There was a large galley for preparing the good food that Great Lakes freighters were known for.

A spartan mess hall for the crew.

Somewhat nicer mess for the officers.

Looking forward towards the wheelhouse. The long amidships portion of the vessel was meant to ship large amounts of loose material-- iron ore pellets-- from the ore mines of Lake Superior to the steel mills of Detroit, Cleveland and Buffalo. Beneath the narrow hatch covers are three colossal cargo holds.

The cargo hatch covers are heavy enough to require their own winch to open them. It travels on rails running the length of the deck. When under way, the clamps along the edges must be properly tightened down to prevent water coming in during storms-- as happened with the Edmund Fitzgerald.

The middle of the three holds is accessible by an observation deck 30 or 40 feet above the bottom. On the opposite side, the holes in the ribs of the ship allow crewmen to move from the front to the back of the ship in high seas, without being washed overboard. The flexible steel hull (this ship was built around the same time as RMS Titanic, with its brittle steel) twists and flexes under the rapid, battering chop of high seas.

The Schoonmaker's wheelhouse is tall compared with most bulk freighters, because she had an extra "Texas" deck as an observation lounge for steel company executives.

The double doors at the deck level open up into a wood-paneled corridor which provided access to the passengers and deck officers quarters. The deck hands had the next level down (currently inaccessible).

The ship's "fireplace" in the passengers lounge at the bow.

Deck officers quarters.

Stairs lead up to a captain's lounge where the ship's master could entertain steel barons like Andrew Carnegie and Colonel Schoonmaker himself.

Located off the lounge, the captain's quarters are large and elegant, but fully equipped with everything the sailing and administration of a large vessel required.

A hidden door leads to a special staircase that provides access to the Texas deck, where steel company presidents might be playing cards, or where the "old man" could keep an eye on the movements of the ship.

The bow, looking downriver towards the recently-built I-280 bridge and the older drawbridge which it replaced. Since the Maumee River is still host to merchant ships from around the Great Lakes and the oceans, this would be a good spot to ship watch.

Up a set of stairs is the unique feature of this vessel and her sister ship: a Texas deck. I can only imagine the high-stakes corporate negotiations that must have gone on here. In the era of vertical integration, manufacturing companies often owned the mines, the mills and foundries, and the factories that built steel products-- and connected them by their own steamship and rail lines.

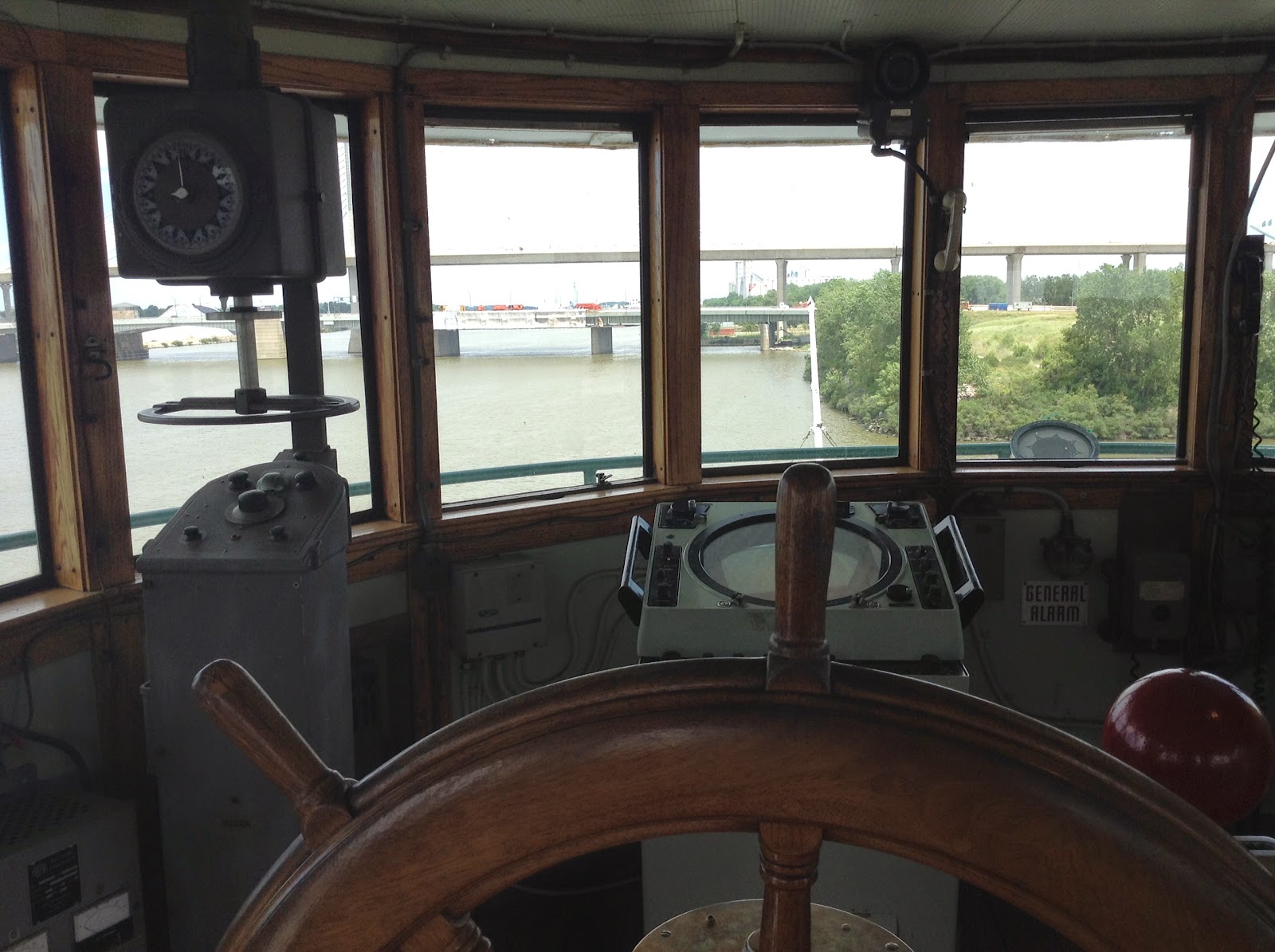

The highest deck is the wheelhouse, where the captain, his mates, and the wheelsmen piloted the vessel down the lakes. Frequently a seaman would make his way up the ranks from deck hand to wheelsman, mate and eventually captain.

Another unique feature of the Schoonmaker and her sister ship were the dual steering wheels. Most freighters only had one in the pilot house. The binnacle in the middle is the original style of compass housing, with two iron balls on the sides to correct for the magnetic disruption of the large northern iron ore deposits in the Great Lakes. Next to it stands a more modern electric compass, similar to that in the captain's cabin.

The pilothouse has become cluttered over time with tools and gadgets such as the radio telephone, radio directionfinders and radar. There's also a brass handle for the steam whistle at right.

The view from the left or port wheel.

The master's chair on the starboard side of the wheelhouse.

A look from the catwalk around the bridge.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.